and

The Appropriate Tune: 'Memories.' by Chromonicci

Anime is big business these days, and a big part of that big success is in what experts call the ‘anime movie’. Call it cringey or kiddy if you want, but there’s no denying that some of the most successful films in recent times have been animated films from Japan. Didn’t that movie based on Demon Slayer make like a billion dollars at the box office? And those two Dragonball Z movies hit number 1 in the U.S., right? Wild.

If you were to ask the average person on the street about the directors of these Japanese animated movies however, the only name you’re likely to hear is Hayao Miyazaki. Which is unfortunate, because even though Miyazaki’s reputation is well earned, reducing any segment of art down to a single creator does a disservice to art itself. So how about we use our anthology movie pick of the Marathon to put a spotlight on some new guys, and a guy that loyal blog readers have seen before.

Released in 1995, Memories was directed by Katsuhiro Otomo, Koji Morimoto and Tensai Okamura, written by Otomo and Satoshi Kon, and produced by Atsushi Sugita, Fumio Sameshima, Yoshimasa Mizuo, Hiroaki Inoue, Eiko Tanaka and Masao Maruyama through Studio 4°C and Madhouse, based on manga by Katsuhiro Otomo. In ‘Magnetic Rose’ (directed by Morimoto) a down-on-their-luck team of salvagers in 2092 respond to a distress signal on an enormous abandoned spacecraft once owned by a famous opera singer, although it seems to be home to something else now. In ‘Stink Bomb’ (directed by Okamura), bumbling scientist Nobuo Tanaka takes an experimental drug to cure his cold only to accidentally become a weapon of mass destruction in the process. Finally Otomo himself takes the lead in ‘Cannon Fodder’, a slice of life story centered around a family in a city so dedicated to warfare that the whole of society is centered around firing cannons, although who exactly they’re firing these cannons at is something of a mystery. Topics such as obsession, the persistence of memory, fascism and how other people at the comic convention feel when you refuse to shower or use deodorant will be addressed.

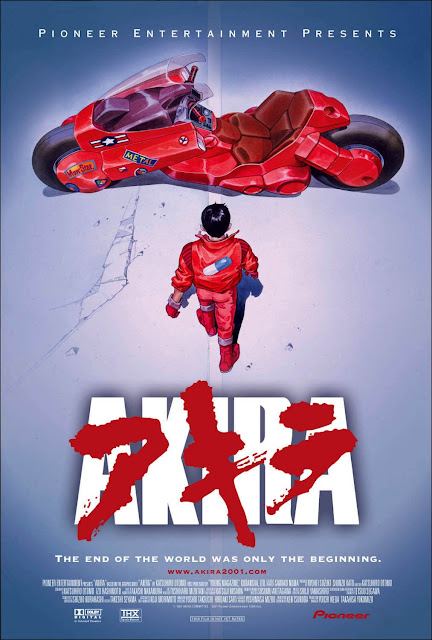

When it comes to anthology films, especially those based on the works of one person, it can sometimes be difficult for each story to stand out. Animation helps to alleviate that problem; While all three stories feature a kind of violent morbidity that feel right inside the wheelhouse of the man behind Akira, the fact that each story features a radically different art style really helps to distinguish one from the other. Magnetic Rose uses a more realist style that modern anime fans would find reminiscent of films like Perfect Blue and Paprika, Stink Bomb is brings to mind the work of Naoki Urasawa (‘20th Century Boys’, ‘Billy Bat’), while Cannon Fodder brings to mind Pink Floyd’s The Wall and Monty Python. Of the three Cannon Fodder looks the most unlike what you’d expect from an anime film, with its heavily shaded, heavily stylized people stuck in a fascistic hell of steam and heavy industry, and it’s the one I like the most. Although at the end of the day all three look good, and they’re all animated with the degree of quality you’d expect from Madhouse, which has gone on to become Japan’s premier anime studio.

Of course in all anthology films there’s always a centerpiece story, whether intentional or otherwise. For the Twilight Zone movie it was NIghtmare at 20,000 feet, and for Memories it’s certainly Magnetic Rose. It’s the longest of the three segments, and certainly the most ambitious in both what it’s trying to say and what it’s trying to show on a visual level. Those coming into this film from Akira will likely find the greatest level of familiarity with Rose as well, high-concept science fiction involving the nature of reality featuring highly fluid animation, and of the three it’s the only one that feels like it could have been expanded into its own feature-length film without much issue. I don’t know if I would have done that though personally, as I think the contrast between Rose and the more comedic, stranger stories really elevates the entire film.

Diverse art styles pair well with diverse music. Anime fans will be pleased to see the name Yoko Kanno as the composer for Magnetic Rose, who would later go on to score the legendary Cowboy Bebop. Jun Miyake provides a little bit of ska for Stink Bomb, and Fumitoshi Ishino of techno group Denki Groove bookends the film with some hard dance beats. It’s a soundtrack made for vinyl, that’s the thing that comes to mind now.

Memories gets the recommendation. It’s not a film on the level of Akira, but then most movies aren’t, but it is a showcase of incredible talent and a love letter to the art of animation. Probably not something you’ll want to watch with the kids, a bit too dark for that, but grab a friend or two this Halloween and you’ll have a good time. Although if you’re trying to watch anime on Halloween having any friends at all might be too much to ask.